Imagine entering an operating room for major surgery and knowing that your team of physicians has already practiced the procedure on a replica of your body. Before you go under anesthesia, you can feel confident that your surgery will be shorter, your recovery time simpler, your risks of complications fewer, and your bill cheaper. With 3D printing entering the medical and healthcare field, this is more possible than ever before.

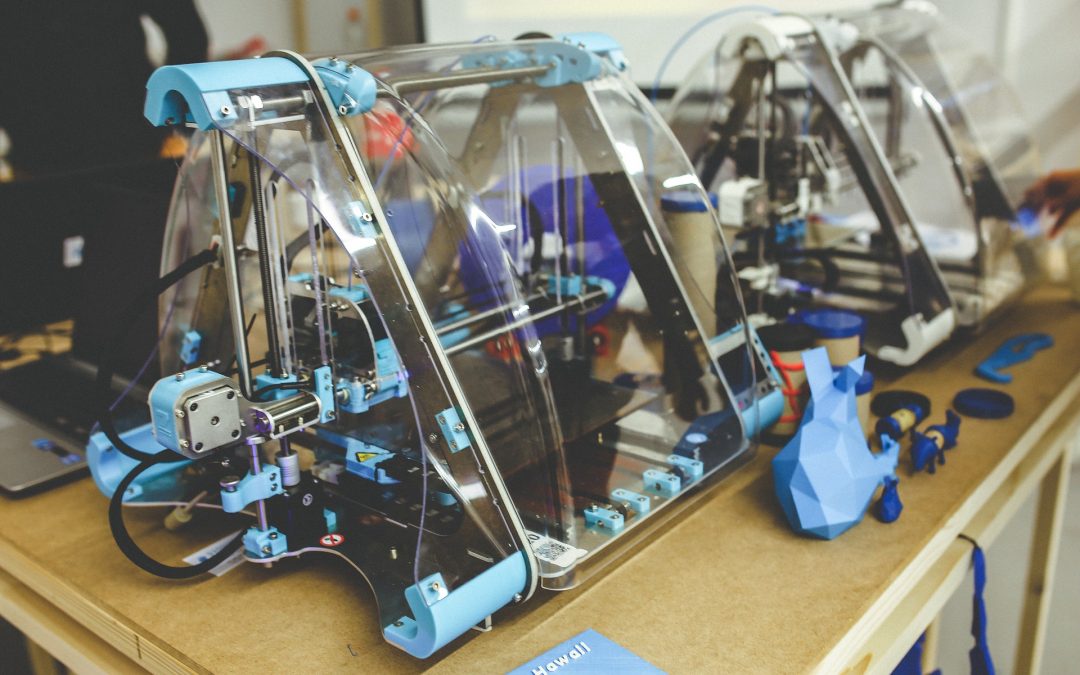

In the past several years, the idea of 3D printing has entered the mainstream as an exciting and futuristic revolution to manufacturing. Unlike traditional printers with ink and paper, 3D printing cuts and shapes various materials such as aluminum, wood, foams, steel, glass, and plastic to create the objects we use daily. Pressing “print” on a new pair of eyeglasses, a car, or furniture sounds like a dream come true. With the many types of 3D printers, this soon may be a reality for the average person.

Even more impressive is the way 3D printing can advance modern medicine. For example, prosthetic limbs from 3D printers can change lives for amputees, or printing replicas of patients’ actual body parts would allow doctors to be familiar with the patient before entering the operating room. 3D printing’s potential is great, but the technology is not without challenges. Before it becomes mainstream in medical settings, there are many issues to solve.

Due to detailed design requirements, 3D printing is time-consuming and expensive. A decade ago when 3D printing was beginning to emerge, each printer costed up to hundreds of thousands of dollars. Even with years of advancements since then, 3D printing is still slow enough to prohibit its use en masse; and while 3D printing has gotten cheaper, it still remains a fairly expensive investment. Therefore, they are typically only used for very complex cases or in organizations with large budgets.

The appeal of 3D printing in medicine is its ability to cater to individuals specifically rather than just the average person, but unfortunately, this makes the process longer and more complicated. The red tape, cost, and technical requirements can make getting 3D models into a physician’s hands a long process. These raise ethical concerns about healthcare access, safety, and capacity in regards to 3D printing’s current usage in the medical and healthcare field.

Despite the downfalls, optimism should be strong for 3D printing, particularly in medicine. 3D printing’s weaknesses are frustrating, but in actuality, its weaknesses are also its strengths. 3D printing requires exact design requirements to make prostheses and replacement organs, and the slow, laborious process of 3D printing lends itself well to the complexity of creating body parts. The capabilities for producing replicas of a patient’s exact anatomy reduces the risk of mistakes during procedures. Even surgical training tools can be made more tailored for specific procedures when created, albeit painstakingly, with a 3D printer.

Organizations like Northwell Health are leading the charge for 3D printing body parts. Allowing surgeons to use these for practice could mean a safer and more efficient surgery for both the hospital and the patient. 3D printing can viably help treat tumors, deformities, amputations, and many more conditions, proving that the use of 3D-printed objects can dramatically improve a patient’s healthcare experience from start to finish.

As 3D printing advances, it is sure to become more efficient and cost-effective. The more we invest in it now, the sooner modern medicine can reap the rewards.